EDITOR’S NOTE: An older version of this post appeared on the Edmodo blog on Medium at this link.

February, March, and April are when universities send students admissions acceptance letters. Accompanying those letters, or following soon after them, come financial aid award letters. These award letters are confusing and opaque. Understanding them is critical as you make decisions on which college to attend and how to pay for it.

It’s better to think of financial aid award letters as college financing plans, which explain how you can pay for an expensive college education. The Department of Education has created a new template called just that, but most universities have not yet adopted it. This template is much more honest and easy to understand.

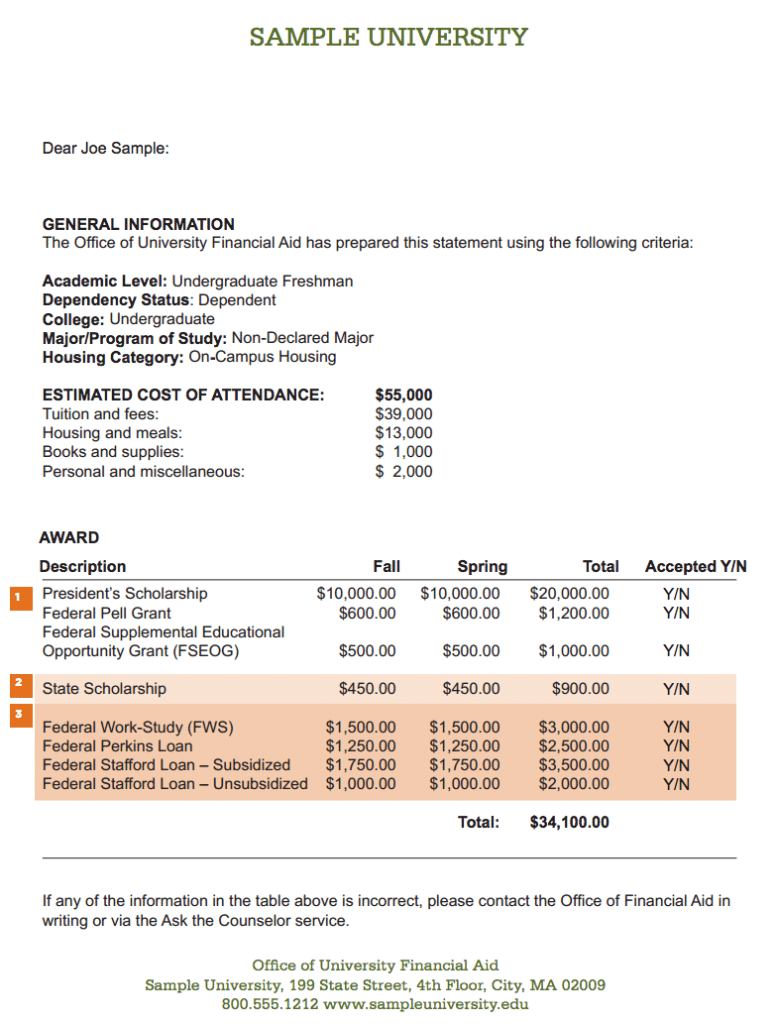

Instead, most universities still use older, more confusing templates like the one below.

Typical Financial Aid Award Letter. Courtesy: Massachusetts Educational Financing Authority (mefa.org).

Total Cost of Attendance

One term that’s often confusing on an award letter is “total cost of attendance (TCOA).” Colleges derive this figure by adding all the different costs of attending: tuition, fees, books, travel, residence, food, etc. But it’s important to understand that:

- These costs are estimates. Tuition costs can vary based on the number of courses—or credits—you take. So some students may end up paying significantly more for tuition than the estimate. Likewise, the cost of books can vary significantly, as can travel costs.

- The TCOA doesn’t include some costs. It doesn’t, for example, count the costs of eating outside of a student’s meal plan . Or the costs of weekend trips or entertainment, which can all add up. So take the time to build your estimate of these costs.

Understanding EFC

On some financial aid award letters, you’ll see the term EFC, which stands for “Expected Family Contribution.” EFC is a technical term, and it refers to the amount of money the government thinks the family should pay for a child’s college education. It’s based on income estimates from your income tax return as well as on asset information from the Free Application for Federal Student Aid or the CSS/Profile.

The EFC is often an unrealistic number. For example, the government believes a family that earns $80,000 a year and has one child in college should be able to pay between $14,000 and $18,000 annually towards a child’s education.

When a university calculates “financial need,” they base that on the difference between the total cost of attendance and the EFC. This difference is the maximum amount of need-based aid for which you can qualify. If you have unique circumstances that justify a lower EFC, read down to the section below on appeals.

Understanding Grants

The distinction between grants and loans on a financial aid award letter is critically important. You don’t have to repay grants, but you do have to repay loans. So when you analyze a financial aid award letter, separate grants from loans. It is always better for a student to receive grant awards.

There are different kinds of grants you might receive:

- Federal Financial Aid Grants: These are awards by the United States government, based on need or service in the military. The US Department of Education has a good summary of these grants, which include Pell Grants and Supplemental Education Opportunity (SEO) Grants for students with financial need, TEACH grants for students who intend to teach and grants for veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

- State Grants: Many states have grants for college as well, and requirements do vary by state, but almost all require you to file the FAFSA and provide some evidence of high school GPA.

- Institutional Grants: These are awards from the specific college you’re attending. Colleges often guarantee these awards for four years, so they’re a great aid in financing an education. And many of them are merit-based, so you can get them even if your EFC is high. But they do come with conditions attached, such as GPAs that have to be maintained. So read the fine print.

Loans: The Hidden Cost of College

Financial aid award letters are most misleading on this count, often counting loans as aid. They aren’t. Loans accrue interest, and you have to pay them back. Loans do not reduce your total cost of attending a university. They defer it.

The presumption is that when they have to be repaid, the student will have an income that benefits from the education he or she received, and can use that income to pay back the loan. But only about half of all college-goers get a degree in six years so that you might end up with the loans but no degree. And student loans cannot generally be discharged even in bankruptcy so that this loan will stay with a student for a long time.

Just as there are different types of grants, there are different types of loans:

- Federal Direct Loans: This is money loaned directly by the federal government, often at subsidized rates of interest. The government will appoint a loan servicer — a company that will track your loan and payments. Some loans (called “subsidized” loans) do not accrue interest or require you to make payments while you’re in college. Others do.

- Private Loans: These are loans from private companies to cover the remaining cost of college. Often these are at higher interest rates and require parents or other adults to co-sign a loan application.

A Template to Evaluate Aid Offers

LifeLaunchr has published a template to aid parents and students in evaluating aid offers. The link to it is here (be sure to make a copy before you use it). You can make a copy of this into a new Google Sheet and use it as you wish. Good luck!

Appeals

There are sometimes circumstances that justify a lower EFC, and higher financial aid, than the FAFSA indicates. These circumstances include divorce, separation, loss of a job or reduced income due to changed hours, the costs of caring for aging parents, loss of some assets, or high medical expenses. If any of these circumstances apply to you, you can appeal a university’s financial aid offer. There’s no guarantee of success, but it’s worth trying. Colleges do aim to be fair within their guidelines, so explaining your situation is critical. Here are a few notes as you craft your appeal:

- Follow the university’s process. Call the financial aid office and ask how you can appeal their aid offer. There may be a form (called a “special circumstances form”) you have to fill out, or they might ask you to write a letter explaining your situation.

- Be polite. Understand that universities have guidelines and can’t always accede to your request. Sometimes the instructions produce unfair outcomes, but still, be courteous to the administrators who are following them.

- Be factual and detailed. In your letter or the form, provide details. Provide figures and tables that show, in as precise a manner as you can, how much your income and expenses are, and how much you can afford. Clear, factual evidence is much more persuasive than emotional appeals.

- Ask the administrators to exercise “professional judgment.” Professional judgment is a technical term in the financial aid universe, allowing financial aid officers to use some discretion under specific circumstances.

- Don’t wait too long. Remember that financial aid is a finite resource, and when there is no more money to offer, there’s no ability to exercise discretion. So act as soon as you can.

consists of the book itself